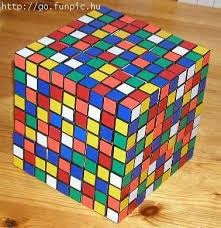

Deeper Strategy – Battlefield Complexity

Slightly

more complicated than the 3x3…

As a result, war

is not governed by the actions or decisions of a single individual in any one

place but emerges from the collective behavior of all the independent parts in

the system interacting locally in response to local conditions and incomplete

information.

-Marine Corps Doctrine Manual on

Warfighting, p.12-13

Human

beings tend toward simplicity where possible. In many ways it is necessary to

our survival and furtherance as societies and countries. Basic assumptions that

hold true in the majority of scenarios allow us to go through life without

pausing for significant thought with each action we take.

In

many ways these actions are good, but there are also negatives that come along

with them. Stereotypes against certain groups of people spring up from this

mindset toward simplicity, as an attempt is made to reduce entire groups of

people to the lowest common denominator. Societies can sometimes stagnate as a

result, because people do not seek new ways to innovate and move forward. In

warfare, generals become complacent as they assume their enemies will continue

to behave as they have in the past.

It

is easy to allow this tendency toward simplicity to affect your gaming aptitude

as well. During the times I’ve played against a single opponent with no

variation, I’ve sometimes noticed that I’ll simply play the last army roster I

constructed, with no thought as to what went right or wrong in the previous

game. This is a constant struggle that we have in the pursuit of effective

competitive play. (It’s probably worth noting that “competitive play” as used

here can be defined as playing a game system with the intention of having

reasonable prospects of victory.)

This

spills out into the Internet discussions of units as well, when army lists and

unit selection are based on a simple checklist of “good” and “bad” selections

in a given army. While it is true that certain units and even armies have

inherent advantages that make them more difficult to overcome, it is not fair

to cast aside a unit based on its performance in a theoretical vacuum. Army

coherency, synergy, and purpose all play a part in determining the

effectiveness of a unit. This is further complicated by the introduction of

Battlefield Complexity.

The

quote at the beginning of this article goes a long way to defining the term Battlefield Complexity. It is the

condition created by the combination of all forces, friendly and hostile, and

their given positions and strengths on the battlefield. Terrain, morale, and a

host of other battlefield conditions factor into the equation as well, so many

in fact that to pretend to quantify them all is madness. These conditions

change with every decision on the battlefield, creating a unique situation and

set of opportunities that will most likely never occur the same way again.

Think

of all the stories you remember from your favorite moments in wargaming. In the

most memorable of moments, you can picture in your mind’s eye the condition and

location of different models across the table, combining to bring about that

one moment you remember so vividly. These conditions are unlikely to be

repeated exactly at any point during

your wargaming career. There are simply too many variables for it to ever

happen quite the same way again.

To

become the most efficient force manager possible, a general must step outside

his assumptions and allow actual battlefield situations to take precedent. In

an example that takes this thought process to the extreme, a squad of Gretchin

is almost unnoticeable in a vacuum in terms of threat. However, when they are

hidden from Line of Sight and holding the winning objective on the final turn

of a game, their threat potential changes completely. While their capacity to

physically damage your forces is perhaps less

than if they were being used to attack, their capacity to threaten your goals

and the outcomes of the battle are greater than ever.

This

is obviously a simple example, as any player can see when they are nearing a

loss in this way. However, battlefield conditions are rarely such a stark

contrast between threat/non-threat. Often, there will be no right or wrong in

pursuing the course for victory; there will simply be a choice that is

perceivably better than another.

I

would also argue that building a battle plan that relies on individual units to

achieve monumental tasks is a good way to set yourself up for failure. There

will obviously be a primary reason for taking certain units, but it is often

better to have several slightly less efficient options, rather than relying on

a single strike to finish the job. As in real warfare, dice interfere with the

best-laid plans, and sometimes even a Titan fails to kill its target.

My

process for building lists in both Warhammer 40,000 and Dropzone Commander is to specialize my units to fulfill a

certain task, building in more redundancies as the points limits increase. My

army is never built around a certain unit; I don’t plan to use my other forces

to protect/defend/support another specific unit in my army. Rather, I build to

accomplish the variety of tasks that may come up in a given game. The units are

included to support and defend other units attached for the completion of an

objective, rather than supporting or defending a given unit by default. The

distinction is small, but it is an important distinction nonetheless. This

varied approach means that your force has an added layer of flexibility to

carry it through casualties and sudden shifts in the battlefield’s state.

An

example comes in the form of my Tyranid army. The pool of Psykers I carry among

my Synapse Creatures is carefully selected to give me a good chance of getting

off the powers I really need in the

Psychic Phase. They are all fairly mobile and fairly resilient, which means

they are interchangeable in terms of which units they support. Depending on

what they roll, this allows me to switch their positioning and role within the

army with each game. Whichever creatures get Paroxysm follow the Hormagaunts up

the field to buff their chances in combat. Those with Catalyst position near my

Flying Monsters to ensure they last as long as possible.

These

are some minor examples in army selection, but the fact is that you cannot know

all possible situations ahead of time. Battlefield Complexity being what it is,

you absolutely must go into the game

knowing that you cannot control all conditions. Flexibility and fluidity will

go a long way to providing optimal chances at success. Each unit must be chosen

for its cohesion with the remainder of the force, and every turn on the

battlefield must be carefully analyzed to see how it fits in with the rest of

the plan. If a plan becomes untenable, the only option to optimize success is

to quickly reevaluate and change your method of pressure. Learning to recognize

these conditions sooner and to react appropriately will make you a better

commander in the end.

+Exorcists+Shoulder+Pad.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment